Conference themesThe snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas have always conjured up the image of an impassable barrier. The constraints and limitations imposed by the topography, climate and ecology are characteristic of the Himalayan experience. Equally distinctive is the way these barriers to social life have been overcome and circumvented in order to connect people through trade, to maintain family, political or religious ties and to allow for the circulation of goods, skills and ideas both regionally and within the world at large. While rivers have long constituted natural pathways for the flow of life, mountain passes supply the air that breathes life into society. Trading routes that crisscross the Himalayas have also been corridors for confrontations and wars that have continuously redefined political borders. The demarcation of state territories and the hardening of national boundaries have often disrupted local livelihoods dependent on seasonal pastoral transhumance, trade and pilgrimage networks. Many historical variables and uneven temporalities have shaped the complex sociopolitical spatialities of Himalayan communities. This range of hills and mountains exemplifies contrasted experiences of mobility and isolation; it has one of the lowest road densities in the world but maintains other forms of connectivity.

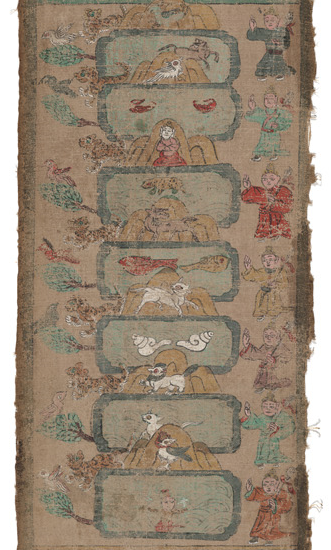

For this conference, we seek to call attention to movement as a particular social dynamic and to explore how it relates to cultural practices, imaginaries and materialities. To emphasise movement and process is not to dismiss place. On the contrary, the deeply historical and changing character of the Himalayan region and of its human settlements needs to be connected with the pervasive delocalisation of social life (Escobar 2008). This type of approach considers mobility and movement, trails, routes and roads as the “connective tissue” within various configurations of “power-geometries” (Massey 1993) and against the backdrop of rooted cultures and identities inscribed in particular landscapes. Movement has been valued differently over time and across cultures, and social and spatial mobilities can also result from inequalities and produce forms of inclusion and exclusion (Adey et al. eds. 2014). We propose to address movement through notions of circulations, pathways and passages. Circulations refers to the movement of men and ideas, of knowledge and techniques, of goods and capital beyond mere trade and mobility as physical motion in reference to long-term relations that are socially transformative for those involved, on different scales or across diverse networks. Investigating circulations as a dual movement of going forth and coming back provides particular insights into forces that change a society (e.g., Stein 1977, Markovits et al. eds. 2003, Tagliacozzo and Chang eds. 2011). In turn, certain pathways as actual lived environments reveal the relative importance and positionality of particular places in relation to circulation networks and systems of exchange (e.g., Saxer 2016). Pathways are made of internal and external constituents that nurture smaller intimate worlds and tie people to particular places and to each other. They are linked to mobile entanglements of people with their historical and contemporary landscapes, as well as to forms of anchoring in the natural environment and culturally valued sites (e.g., Van Spengen 2004, Smadja ed. 2009). The experience of circulation and presence on or along these pathways, as well as of their varied temporalities, also establish a passage understood both as a liminal zone and as a breaking point between two worlds, such as the mountain pass: a path through a space and a crossing of boundaries. What does the study of circulation tell us about the Himalayas and their social and spatial dynamics? Does the Himalayan social fabric produce peculiar circulatory regimes and pathways? And with the growing number of communications and passages across geographical constraints, how are frontiers and boundaries actualised and territories redefined? How have relations between states and circulatory phenomena evolved? What are the new cultural and moral geographies that emerge from this global-cum-local circulation? And as Himalayan roads, just like other roads, materialise power relations, what is their colonial legacy, how have they become postcolonial, and what promises do they uphold? Journeys are passages to elsewhere, which reveal cultural anchorage points and identity boundaries; they open onto the possibility of encounters. The bundle of interrelated notions that we propose as a framework allow for a multiplicity of angles of analysis, from the supra-national level to the local, which examine circulations, pathways and passages in all the dimensions of their physicality and imagination. We hope to focus our collective explorations on the following lines of inquiry, and invite submissions that contribute to the following three themes: Journeying: Landscape, Ancestral Roads and Other GeographiesJourneys and the paths they follow contribute to generating a social landscape that tells of communities’ histories and to linking bodies, movement and place. The trajectories that people follow, the way in which they move across the physical landscape and experience it, the temporality of this movement and the sequences in which places along the way are encountered may be fundamental to people’s experience of their material and spiritual environment (e.g., Ingold 2007, 2011; Smadja ed. 2009; Tilley and Cameron-Daum 2017). Trails and travel are a fundamental aspect of placemaking and of forms of belonging that transcend geographical boundaries. Cultural metaphors of identity can be materialised in vernacular geographies for which powerful places or “potent landscapes” are cumulative and are historical matrixes of places and pathways (Allerton 2013) linking past and present, the living and the dead. There is a complex entanglement of landscape with human lives made up of a mingling of ancestral and personal day-to-day movement and mobility. Besides everyday practices and the embodied experience of place, the history of human settlement in the Himalayas and the prolific oral traditions and narratives about these movements across the landscape also provide rich material to reflect on (Huber and Blackburn eds. 2012). In many traditions across the Himalayas, the memories of these “lines of travel” are reiterated in after-death journeys often conceived as reverse migration, a return to a place of origin, an ancestral homeland. The geographies of such journeys reveal an organisation and valuation of spaces and places, a mapping of ancestral roads, which is sometimes linked to concrete landscapes along a migration timeline, or can even be materialised, like the long scroll (the “God’s road”) used during funerals by the Naxi people to guide the soul of the deceased: the scroll is like a bridge that the soul crosses to reach the realm of the gods, and the structure of writing in these texts imitates the structure of walking (Mueggler 2011). While ritual journeys are typical of shamanic traditions, pilgrimage is a common Buddhist and Hindu practice throughout the region in which the outward journey is also simultaneously the path to an internal purification. Here movement itself along pilgrimage routes and its circularity are generative of a different kind of journey, an experience from which women are sometimes excluded, such as on some of the circumambulation routes of the ‘Pure Crystal Mountain’ in Tibet’s Tsari region (Huber 1999). The various ways of journeying, both past and present, and their many motivations reveal processes and perceptions that engender a sense of place, of territorial belonging and of boundaries. A detail of the top section (the realm of the gods) of the Naxi “God’s road” (Ha zhi p’i) funeral scroll. This 39½-foot long by approximately 1-foot wide scroll is made of homespun hemp cloth in gouache painting. Source: Library of Congress. Digital ID: asnaxi nzs001. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.asian/asnaxi.nzs001 While promoting an outward-looking understanding of place, we welcome reflections that privilege routes rather than roots, or propose a fresh look at their articulation. How do roads and paths simultaneously enact a sense of place and a connective potential? Transportation and speed certainly affect people’s relationship to their environment and modern roads belong to a different way of conceiving and managing space and of acting in it. Could the road itself be attributed form of agency (Rest and Rippa 2019) as part of the “potent landscape” through which people have evolved? Assembling: Roadwork and the Social Life of InfrastructuresIf we look at the Himalayas through the trails, pathways or roads that traverse them, which can be perceived as infrastructures playing on the distance and time between things and humans, the mutual constitution of social relations, forms of knowledge and the material environment produce various assemblages. Roads can be seen as “stretched out spaces of social relations” (Wilson 2004) and as key elements of technopolitical apparatuses that condition the “possibility of exchange over space” (Larkin 2013). These infrastructures tell us about the territorial vision of states and the latter’s efforts to assert their sovereignty as part of “regimes of territorialisation”, as emphasised in recent research conducted in Nepal (Rankin et al. 2017), but also about heterogeneous networks (market, labour, expertise, etc.) that operate at differing levels beyond their built form. Since the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) came into being, the issue of roads and connectivity in the Himalayas and beyond (Highland Asia, Central Asia) has galvanised the emerging field of “roadology” (Zhou 2016) and the fast‑growing scholarship on infrastructure. New routes have either replaced historical pathways crossing the Himalayas or created new corridors and have become agents of change. Building roads has more than ever become a government motto synonymous with connection, development and wealth, symbolising the current neo-liberal ideology of mobility as a sign of adaptability, autonomy and agency. There is a common belief that roadless territories cannot embrace globalisation and that tarmac is the visible sign that elected governments take care of local communities who will benefit from new connections with the outer world. Everyone needs a road.

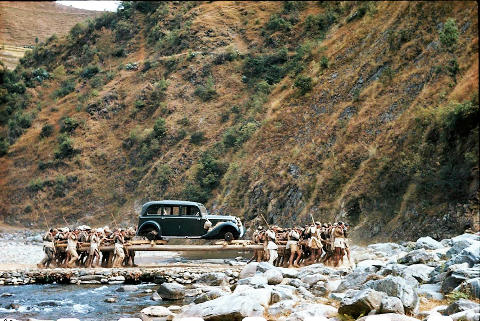

Porters transport a car on long poles across a stream in Nepal, 1948. This photograph was taken in 1948 by the German American photographer Volkmar Wentzel and published for the first time in 1950 on the National Geographic magazine. To varying degrees, forms of globalisation and the circulation of goods, people and ideas largely predate modern technologies. Nevertheless, road narratives insist on promises for a better future, considering them as a path towards modernity, development and proper integration. They may symbolise the presence of the state and the visible and physical site of government actions. Roads are also places where people work to build or maintain these infrastructures (Murton ed. 2019), and they can be considered as always being “in the making” and as having their own temporality (Joniak-Lüthi 2019): their close surroundings are forever evolving with the broader political and economic forces that shape their destiny. Roads are distributed unequally, however, and can prove to be a “technology of distantiation” (Pedersen and Bukenborg 2012), just as remoteness and disconnection may also be a state tool (Gohain 2019). Roads being ambivalent successes and failures, we are also interested in the demise of roads, those that have not resisted the monsoon and have fallen into ruin (see Gupta 2018), those that end up nowhere, or become dead-ends both literally and metaphorically. As a particular assemblage of power/knowledge, to what extent are roads profitable, and for whom? The transformative power of roads is often overestimated but, when roads are considered as processes (Anand, Gupta, and Appel 2018), they undoubtedly not only transform landscapes, create unexpected disruptions in the geomorphology of the mountains, but also produce well-documented social effects, whether positive or negative, on people and places. Besides the geopolitics of road-making as such, what comes across as lacking in the literature is close scrutiny of locally lived realities of what is (dis)connected, and how. The complex interweaving of relations between state strategies and rationalities of road building and local practices, and the articulation of several scales of analysis enabling one to grasp the dialectics of influences and power that are embodied in the road as a much sought-after infrastructure – sometimes imposed but rarely neutral in terms of local power dynamics – deserve further research. Are roads comparable political arenas? If not, how do they differ? What kind of spatial, political, economic, cultural or social entanglements are roads part of, and how do they diverge from those of other forms of circulation? What do roads, as particular kinds of infrastructures, assemble in unprecedented ways? Crossings: Fantasies and ConflictsRoutes and roads are sites for trade and exchange, for departure and arrival, and also often sites of expectations, competition and conflict. They convey human relationships and become places bearing values that can vary with the history of the road. Roads can become sites of protest, whether the disputes relate to the road itself (its relevance, quality, (in)ability to fulfil expectations), or whether the road becomes a means of action. Bandas (closures) of roads are common in South Asia, where halting the circulation of goods and people has become a regular way of making demands.

Figure 3: Locals planting rice saplings on a muddy road on the occasion of National Rice Day to protest against the sorry condition of the road, in Thamel, Kathmandu, on Thursday, June 29, 2017. Photo: The Himalayan Times. https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/national-rice-day-marked-2 Roads as objects of desire convey hope for better livelihood opportunities and a longing for change, especially in remote rural settings. This is where the ethnography of local road development projects often displays a counter-narrative of the road and how it is viewed locally (Blaikie et al. 1977, 2002; Campbell 2010, 2013). The analysis of tales of connectivity and development thus exposes road ideology and state visions that may run counter to local imaginations of connectivity. The desire for greater accessibility that materialises in the road with its promises and dreams of development also comes with threats and fears. The road procures “surprising worlds” (Dalakoglou and Harvey 2012) and can become an “excessive fantastic” object, which in turn creates a kind of enchantment and “awe in autonomy of its technical function” (Larkin 2013:333) as it exercises power over people’s imagination and affects. A qualitative approach invites us to consider the various instances of the movement of people, goods, ideas (but also skills or spirits) in relation to different geopolitical orders, value regimes and cultural or ontological frames of reference. Roads and circulation pathways tend to carry people away across time, space and embodied differences of culture and language; they are connected sites across which new values are formed and transmitted. As such, they enable crossings and nurture a longing to become otherwise. How do these crossings produce new subjectivities? What conflicts do they generate? What new circuits of belonging do they facilitate? ReferencesAdey, Peter, David Bissell, Kevin Hannam, Peter Merriman, and Mimi Sheller, eds. 2013. The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities. London: Routledge. Allerton 2013. Potent Landscapes: Place and Mobility in Eastern Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel. 2018. The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478002031 Blaikie, Piers, John Cameron and David Seddon. 1977. The Effects of Roads in West Central Nepal: A Summary. Norwich: University of East Anglia. Blaikie, Piers, John Cameron and David Seddon. 2002. 'Understanding 20 years of change in West-Central Nepal: continuity and change in lives and ideas.' World Development 30(7): 1255–1270. Campbell, Ben. 2010. ‘Rhetorical Routes for Development: A Road Project in Nepal’. Contemporary South Asia 18 (3): 267–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935. Campbell, Ben. 2013. ‘From Remote Area to Thoroughfare of Globalisation: Shifting Territorialisations of Development and Border Peasantry in Nepal’, in Territorial Changes and Territorial Restructurings in the Himalayas, edited by Joëlle Smadja, 269–85. New Delhi: Adroit Publishers. Dalakoglou, Dimitris, and Penny Harvey. 2012. ‘Roads and Anthropology: Ethnographic Perspectives on Space, Time and (Im)Mobility’. Mobilities 7 (4): 459–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2012.718426 Escobar, Arturo. 2008. Territories of Difference: Place, Movement, Life, Redes. Durham: Duke University Press. Gohain, Swargajyoti. 2019. ‘Selective Access: Or, How States Make Remoteness’. Social Anthropology 27 (2): 204–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12650 Gupta, Akhil. 2018. ‘The Future of Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure’. In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, 62–79. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Huber, Toni and Stuart Blackburn, eds. 2012. Origins and Migrations in the Extended Eastern Himalayas. Leiden, Boston: Brill. Huber, Toni. 1999. The Cult of Pure Cristal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ingold, Tim. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge. Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge. Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka. 2019. ‘Introduction: Infrastructure as an Asynchronic Timescape’. Roadsides 1: 3–10. https://doi.org/10.26034/roadsides-20190012 Larkin, Brian. 2013. ‘The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure’. Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522 Markovits, Claude, Jacques Pouchepadass and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, eds. 2003. Society and Circulation: Mobile People and Itinerant Cultures in South Asia, 1750–1950. Delhi, Permanent Black. Massey, Doreen. 1993. 'Power-Geometry and Progressive Sense of Place.' In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Changes, edited by Jon Bird, Barry Curtis, Tim Putnam, George Robertson, and Lisa Tickner, 59–69. London: Routledge. Mueggler, Erik. 2011. The Paper Road: Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press. Murton, Galen, ed. 2019. 'Labor'. Roadsides (002). https://roadsides.net/collection002/ Pedersen, Morten A., and Mikkel Bunkenborg. 2012. 'Roads that Separate: Sino-Mongolian Relations in the Inner Asian Desert.' Mobilities 7(4): 555–569. Rankin, Katherine N., Tulasi S. Sigdel, Lagan Rai, Shyam Kumar, and Pushpa Hamal. 2017. ‘Political Economies and Political Rationalities of Road Building in Nepal’. Studies in Nepali History and Society 22 (1): 43–84. Rest, Matthäus, and Alessandro Rippa. 2019. ‘Road Animism: Reflections on the Life of Infrastructures’. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9 (2): 373–89. https://doi.org/10.1086/706041 Saxer, Martin. 2016. 'Pathways: A Concept, Field Site and Methodological Approach to Study Remoteness and Connectivity.' HIMALAYA 36(2). https://digitalcommons. Smadja, Joëlle, ed. 2009. Reading Himalayan Landscapes Over Time: Environmental Perception, Knowledge and Practice in Nepal and Ladakh. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry (Collection Sciences Sociales 14). Stein, B. 1977. 'Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Country.' The Journal of Asian Studies 37(1): 7–26. Tagliacozzo, Eric and Wen-Chin Chang, eds. 2011. Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia. Durham: Duke University Press. Tilley, Christopher and Kate Cameron-Daum. 2017. An Anthropology of Landscape: The Extraordinary in the Ordinary. London: UCL Press. Van Spengen, Wim. 2004. 'Ways of Knowing Tibetan Peoples and Landscapes.' Himalaya 24(1). https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol24/iss1/18 Wilson, Fiona. 2004. 'Towards a political economy of roads: Experiences from Peru.' Development and Change 35 (3): 525–46. Zhou, Yongming, ed. 2016. Roadology: Roads, Space, and Culture《路学:道路、空间与文化》. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press.

|